LA INÉDITA BY SANTOS HERNÁNDEZ, 1935

REDISCOVERING A MUSICAL TREASURE, BUILT FOR ANDRÉS SEGOVIA

A CHARITY AUCTION WITH BONHAMS CORNETTE DE SAINT CYR

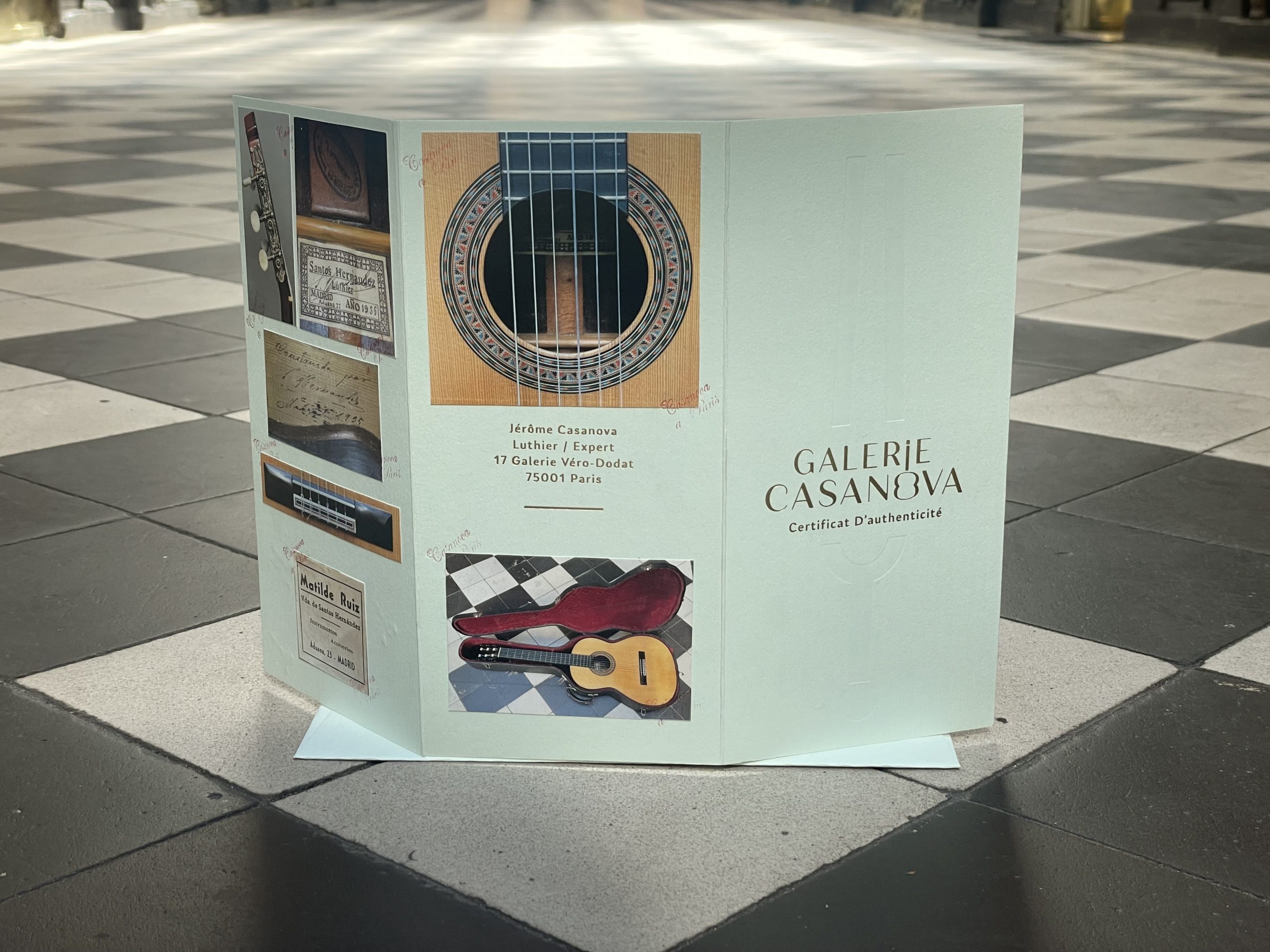

We are pleased to announce the online auction of the legendary La Inédita guitar from May 19 to 28, 2025, in Paris, by Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr, appraised by Jérôme Casanova, consulting luthier-expert. (Estimate: €125,000 – €185,000)

Crafted in Madrid, Spain, in 1935 by legendary luthier Santos Hernández (1874-1943) especially for Andrés Segovia, the renowned Spanish virtuoso, this classical concert guitar has an extraordinary history and is rightly considered a masterpiece of lutherie. By a twist of fate, this exceptional instrument never reached the hands of the musician to whom it was destined, remaining shrouded in mystery for decades. Now, this lost treasure has been rediscovered thanks to its owner, Paco Arango, who wishes to donate the proceeds to the Fundación Aladina.

This guitar condenses the five factors that make it an object of particular interest: its rarity, its provenance, its state of preservation, its cultural dimension and its qualities as a remarkable musical instrument, which are unique to it.

INTRODUCING LA INÉDITA

This is an exceptional classical concert guitar crafted by Santos Hernández (1874-1943) known as La Inédita, made in Madrid, Spain, in the year 1935. It bears the original label glued inside with the following inscription: Santos Hernandez | Luthier | Madrid | Aduana 27 | AÑO 1935. Made for guitar concertist Andrés Segovia.

We also find the luthier’s stamp on the heel of the neck inside the body with the inscription SANTOS HERNANDEZ | ‘’LUTHIER’’ | Aduana, 23-MADRID; as well as his annotation handwritten in ink under the soundboard: Construida por | S Hernandez | Madrid 1935

The rosette, which is a work of art in itself, is made of alternating black and white binding, in the center of which is a blue and red wheat motif, surrounding the main micro-marquetry motif forming red, black and blue triangles.

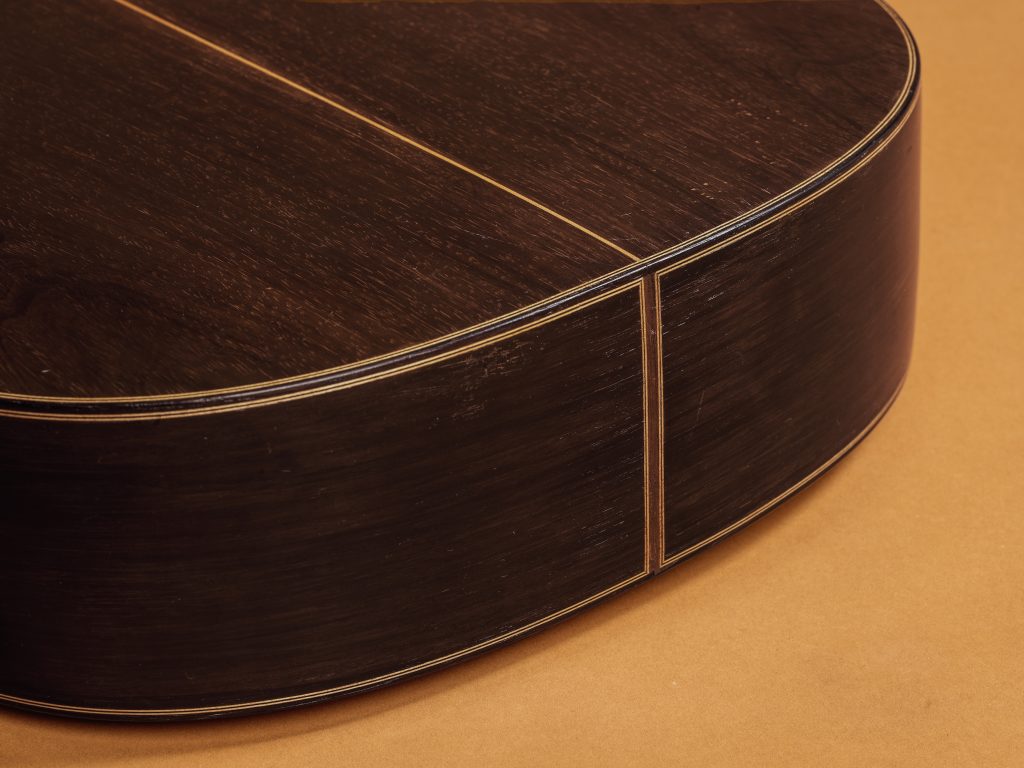

The spruce soundboard is made up of a five-strand fan bracing, the central one of which is continued by two (original) cleats, the lower section is closed by two diagonal strands, the upper part consists of an oblique sound bar; neck and headstock made of cedro ; ebony fingerboard; back, sides, bridge and head veneer in Brazilian rosewood; bridge ornementation made of bone, rosewood and colored wood bindings; very fine shellac varnish; the entire body of the instrument is bordered with simple bindings alternating light wood and ebony and the back joint is decorated with a light wood binding; original tuners with engraved plate and decorated with a lyre, with mother-of-pearl buttons.

We notice – as is frequently the case on guitars of this period, due to hygrometric variations – on the soundboard: under the bridge, two thin splits a few centimeters long, as well as a thin split between the bridge and the soundhole along the central sound bar; we also note a split on the soundboard along the edge of the fingerboard on the bass side; and the addition of a bit of canvas measuring ~1 cm by 2 cm along the central brace. Some light signs of use.

Nut spacing: 51 mm / Scale length: 654 mm / Weight: 1444 g

Exceptional original and well-preserved condition.

The guitar is presented in its original case with its label Matilda Ruiz | Vda. By Santos Hernández | Instruments | Accessories | Aduana, 23 – MADRID

Accompagnied by its certificate of authenticity by Jérôme Casanova

SANTOS & SEGOVIA - BACKGROUND OF LA INÉDITA

The relationship between Santos Hernández and Andrés Segovia is almost as old as the careers of these two figures in the Spanish musical landscape of the early 20th century: their first introduction dates back to 1912, when a young Andrés Segovia (19 at the time) visited Manuel Ramírez’s workshop with the intention of renting an instrument for his upcoming performances in Madrid. The master ordered one of his best workers to present the musician with a recently completed instrument—this worker was none other than Santos, and the guitar was crafted by his hand.

Intended for the musician Antonio Jiménez Manjón, the instrument originally featured an atypical construction with 11 strings specially requested by Manjón—but, due to the client’s reluctance to pay the bill, the guitar was returned to the workshop to be converted into a 6-string model. It was following this modification that the guitar was placed in the hands of Segovia, who immediately fell under its spell and, after hours spent going through his repertoire in front of the audience gathered in the workshop, made it his own. This encounter between Segovia and Santos’s guitar was absolutely seminal for the concertist’s burgeoning professional career, since it was with this same instrument that he would perform his first major successes, notably the performance on May 6, 1913, at the Ateneo in Madrid.

Over the following years, the relationship between the two men continued: Santos performed the maintenance and adjustment of the guitar built by Ramírez in 1922, applying his own label to the back of the guitar alongside that of the Madrid master; then in 1924, he made a new instrument for Segovia, a substitute in case his main guitar failed. We have no record of their exchanges between the late 1920s and early 1930s, but everything picks up in 1935, when Santos completed a new instrument intended for him.

In the meantime, Segovia, like many artists, was tempted by the instruments of other luthiers, notably those of Hermann Hauser I – whom he put in competition with Santos by singing the praises of the Bavarian luthier. These claims largely explain the discord that erupted between Segovia and Santos: the luthier’s ego was so bruised by his client’s irreverence that he refused to deliver the newly finished guitar! Thus began the improbable journey of this new instrument which, despite itself, was put aside and kept away from the eyes and hands of guitarists, contributing to the posterity of what would be called La Inédita…

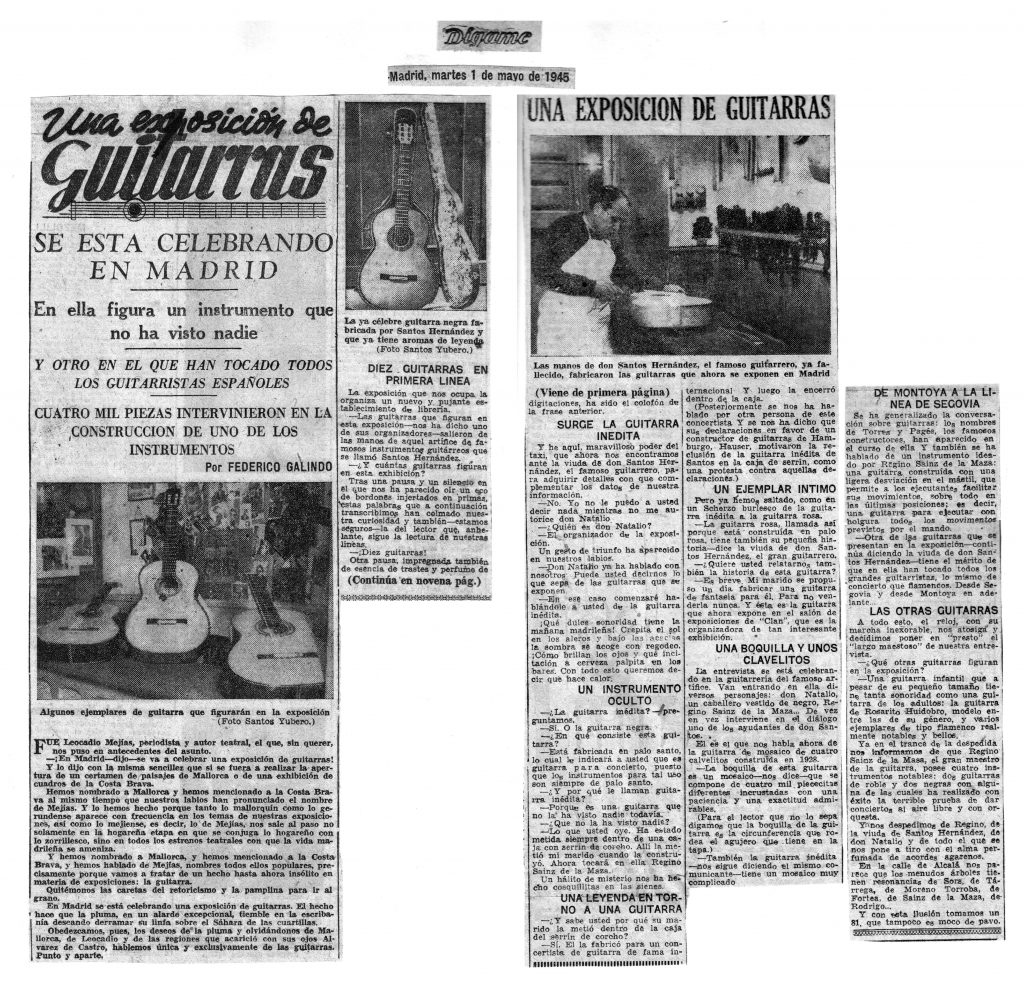

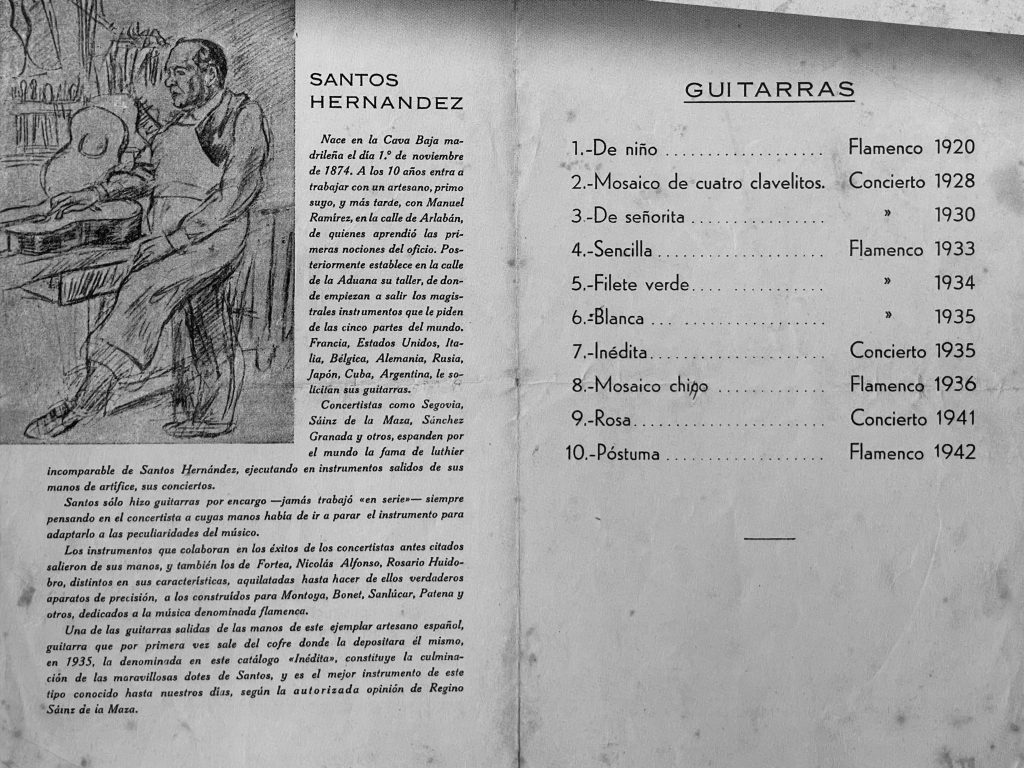

The most eloquent account we have of this mysterious instrument comes directly from Matilde Ruiz, Santos’s wife, who would take over the business after her husband’s passing in 1943. In 1945, she organized an exhibition in Madrid as a tribute to Santos, during which ten of his guitars were presented—among them, in seventh place, one entitled La Inédita … Concierto 1935 .

In an interview published on May 1, 1945, in the newspaper Dígame, Matilde Ruiz stated the following: « “It is a guitar that has never before been seen […] It has always been in a box with granulated cork. My husband placed it there after he finished building it […] He had made it for a world-renowned guitarist, then he locked it in the box.” The Dígame journalist further elaborated: “[…] someone told us about this concert guitarist and how his praise in favor of a luthier from Hamburg, Hauser, had led Santos to ‘seclude’ La Inédita guitar […] as a sign of disapproval against those statements.”

And what a misfortune befell this otherwise promising instrument, specially crafted by the maestro guitarrero for a concert performer of Segovia’s stature. It is important to keep in mind that in 1935, Santos was at the height of his career and like any luthier, his goal was to produce with each guitar an instrument that surpassed the previous one—although, after decades of work, this desire to excel was actually reflected in various iterations of Santos’s talent, so much so that, despite their differences, all his guitars may be considered equal. In particular, his concert model encapsulates all of his expertise to create a tool of great precision and sensitivity for use by particularly demanding musicians. Whether in the choice of materials, the outside aesthetic, or the internal architecture that determines the type of sound, all these elements reflect the total mastery of exceptional lutherie.

A parallel can be drawn here with the violins of Cremona and their illustrious luthiers: if these instruments are still used today several centuries after their creation, it is because they are the perfect channel allowing the greatest musicians to fully express themselves in their interpretation of the repertoire, from the Baroque era to the present day—proof, if any were needed, that these great violins are free from obsolescence. The same is true of Santos’ guitars, eminently relevant in their time and able to translate the desire for pure musical expression of artists such as Segovia. The Inédita is a testament to this: a truly modern instrument.

The guitar was finally passed along in the 1970s by Esperanza Ruiz, niece of Santos Hernández and Matilde Ruiz, to Placido Arango Arias – a Spanish-Mexican businessman, art collector, patron, and president of the Prado Museum’s board of trustees – under equally unusual circumstances. As a great art connoisseur, he understood the importance of Santos’s work and the central place occupied by La Inédita. He was informed of the existence of this guitar and encouraged to acquire it by his friend, art advisor, and gallery owner Fernando Guereta. However, the transaction was not a done deal, as the family initially intended on keep the guitar. It was only after extensive negotiation that Esperanza Ruiz finally agreed to the sale – after demanding from the buyer a staggering sum of one million pesetas, expecting to be met with refusal – but against all odds, he accepted her conditions and concluded the acquisition of this historic jewel. La Inédita has been kept to this day by the buyer’s son, Paco Arango, who has now decided to part with it to fund the charity Fundación Aladina, which supports children fighting cancer and of which he is the founder.

HISTORY OF SANTOS HERNÁNDEZ AND HIS GUITARS

The name Santos Hernández Rodríguez (1874-1943) stands among the greatest in the pantheon of Spanish classical guitar, alongside Antonio de Torres (1817-1892) and Manuel Ramírez (1864-1916). And for good reason: his contributions to the development of the instrument in the early 20th century are immeasurable, so much so that his discreet and refined lutherie work was copied and imitated by both his contemporaries and all generations of luthiers who came after him.

Born in 1874, Santos Hernández entered the world of lutherie at an early age: according to various sources, he was introduced at the age of 12 to the workshop of Valentín Viudes (c. 1863), a craftsman close to his family, with whom he remained as an apprentice until the beginning of the following decade. Around the age of 25, after his military service, he was recruited by Manuel Ramírez (younger brother of José Ramírez), one of the most eminent luthiers of the early 20th century who himself was in the direct line of Antonio de Torres, of whose instruments he produced facsimiles that were the first of their kind. It was alongside Manuel Ramírez that Santos saw his talent flourish, becoming one of the Madrid master’s most loyal workers -loyalty that would see him elevated to the rank of foreman.

The instruments he produced during this period enjoyed a great reputation, and even entered the legend of Spanish guitar since one of them, built in the year 1912, would be end up in the hands of Andrés Segovia (1893-1987), still young at the time but whose fame would soon take off. It was this same instrument that was maintained by Hermann Hauser I (1882-1952) during one of Segovia’s visits to Germany, allowing the Bavarian luthier to study it in detail and assess the work of his Spanish counterpart—and, by incorporating some of the observed elements into his own guitars, contributed to the spread of Santos Hernández’s style outside of Spain.

In 1921, a few years after Manuel Ramírez’s death, Hernández established his own business at Aduana 27 in Madrid (the street numbering would later be changed, as such later labels would appear bearing the number 23). With some thirty years of experience, the majority of which he spent with Mr. Ramírez, he continued building high-end instruments until his final days in 1943. According to a study of his workshop ledgers, it is estimated that his production averaged around twenty instruments per year, mainly consisting of cypress flamenco guitars, and around ten rosewood concert guitars. Built in 1935, la Inédita is one of these higher-grade models: it is made of select materials, including Brazilian rosewood for the back and sides, an imported wood species that necessarily implied a significant cost for the finished instrument. It also features a tuning machine headstock, another expensive element since it requires the work of a specialized craftsman other than the luthier—unlike instruments with wooden pegheads.

In addition to his well-known connection with Andres Segovia, Santos’ guitars were played and brought to their peaks by the most illustrious and talented instrumentalists of his time: both in the classical register with Regino Sainz de la Maza (1896-1981), performer of the famous Concierto de Aranjuez, which he premiered in Barcelona in 1940 with a Santos guitar dubbed La Rubia; and in the flamenco style with Ramón Montoya (1880-1949), initiator of modern flamenco technique, the foundations of which he laid in a 1936 recording using another Santos guitar, La Leona (built while he was working for Ramirez). Finally, let us mention the Romero family, also great endorsers of Santos’ guitars and who ensured their popularity in America, testifying to their international reach.

Through these artists and many others, it is undeniable that Santos’ guitars have left an indelible mark on the Spanish musical landscape of the 20th century, and in this sense they are practically inseparable from the sound of this music as we know it through the recordings of the time and as it is still practiced today, testifying to the great modernity of Santos already in his time and the persistence of his work through the decades. The same can be said regarding the formalization of the visual attributes and dimensions of the Spanish guitar: the style of the rosettes, finely executed, and the general shape of the instrument (dimensions, bracing, etc.) are all attributes that we obviously associate with the contemporary Spanish guitar and which can largely be traced back to the work of the maestro guitarrero.

Santos’ guitars have become true heritage and cultural objects, arousing both fascination and envy from all those that have looked into the matter—as such, many of them are preserved in the world’s greatest museums and private collections. These include the famous 1912 guitar once owned by Andrés Segovia, now housed at the Metropolitan Museum in New York; a sublime flamenca model, dated to 1931, part of the collection of the Musée de la Musique in Paris; Santos’s personal guitar known as El Bombón, built in 1903, long kept by the luthier’s descendants and now part of a major American collection; another guitar, also in the family for decades, is now in a private collection in Japan—this model is renowned for possessing one of Santos’s most beautiful rosettes, featuring a carnation motif, earning it the nickname La Clavelitos. And numerous other guitars that are owned and played by musicians throughout the world…

Among this first-class roster, La Inédita stands out as an exception: despite the rich narrative surrounding its genesis and history, it is one of the few Santos models to have stayed shrouded in mystery and legend for so long, and whose posterity remained more than uncertain. Its recent reappearance concludes a 90-year-long epic, while at the same time displaying Santos’s work pushed to its utmost intensity – or as Regino Sainz de la Maza, one of the few to have laid hands on this instrument in 1945, put it: “La Inédita constitutes the culmination of Santos’s marvelous talent and is the best instrument of this type known to date”.

THE ALADINA FOUNDATION

More than just a historic rediscovery, the sale of the Inédita takes on a deeply meaningful dimension: this exceptional guitar will be offered at a charity auction, with all proceeds going to the project Casa Aladina of the Aladina Foundation. Dedicated to improving the lives of children and adolescents battling cancer, Casa Aladina provides emotional, psychological, and material support to young patients and their families in hospitals across Spain.

Bibliography

Alberto Martinez, Santos Hernandez – 1874-1943 – Maestro guitarrero

Sinier de Ridder / Jérôme Casanova, La guitare espagnole – 1750-1950

José L. Romanillos / Marian Harris Winspear, The Vihuela de Mano and the Spanish Guitar

Sheldon Urlik, A Collection of Fine Spanish Guitars from Torres to the Present

Stefano Grondona / Luca Waldner, La Chitarra di Liuteria – Masterpieces of Guitar Making

Brian Whitehouse, The Ramirez Collection – History and Romance of the Spanish Guitar

S.I.E. CO.,Ltd., Guitar Collection in Japan – 26 Classical Guitars 1831-1999

Museo Municipal Madrid, La Guitarra Española – The Spanish Guitar